What is well-being?

The term “well-being” is often heard these days. Our institute’s motto is to be able to feel well-being on Awaji Island. Now, well-being has become a word that is often mentioned both in Japan and abroad. The latest comment section of the scientific journal Nature magazine also contains an interesting statement about what well-being is. “Why we need to measure people’s well-being-lessons from a global survey”, Nature (2025) May 1st. vol 641, p34 by T.J. Vander Weele and B. R. Johnson, (Why we need to measure people’s well-being-lessons from a global survey). Using this article as a reference, we would like to explore what well-being is.

Whether one’s daily life is happy (well being) or satisfying is an important issue for everyone. Of course, it is also related to the politics and natural environment of the country or region to which one belongs. In response to this, this question is asked all over the world, and whether the local people are happy is reported in the news. The representative of such questions and surveys is conducted by Gallup, an American company. This is a survey that measures the engagement (enthusiasm toward work) of employees of an organization, and based on the results, it is known which country’s residents feel the happiest and as a result are enthusiastic about their work. According to this result, Nordic countries always rank high in the countries with high happiness. However, it can be imagined that happiness is actually not easy to measure. This is because it is easy to imagine that there is a difference in happiness between people in Nordic countries and tropical countries or countries with large religious differences. In fact, Dr. Vander Weele of Harvard University, who made the above comment, and his colleagues conducted a happiness survey of 220,000 people in 22 countries around the world and found that happiness varies depending on national conditions, economic differences, age, etc.

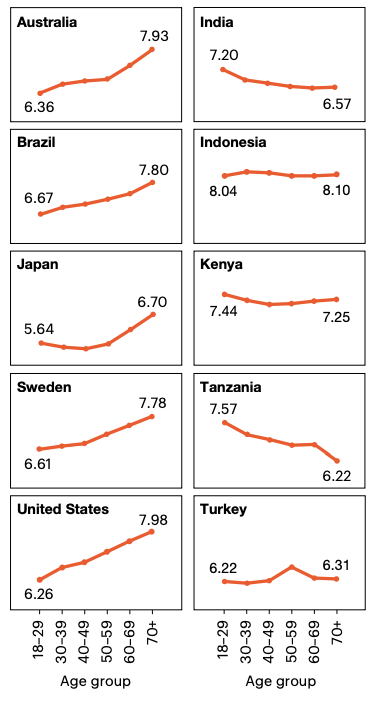

Let us give you an example. When the degree of happiness was divided into 10 stages and a survey was conducted on 10,000 people in each of 22 countries by age, it was found that there were large differences in countries and ages. As shown in Figure 1, in Australia, Brazil, Japan, Sweden, and the United States, the degree of happiness is relatively low when young, and is highest in the 70s. On the other hand, in India, Indonesia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Turkey, there is little difference by age, or it is even lower in the elderly. This is naturally due to the economic situation, political situation, and religious background of each country. In economically advanced countries, the elderly probably have more economic savings than their younger counterparts, and as a result, their sense of happiness is also increasing. Interestingly, it was found that young people in these countries have lower happiness levels. From this, it can be inferred from the survey that young people in these countries, including Japan, need more mental care than the elderly.

Fig. 1 Degree of happiness depending on country and age. (by T.J. Vander Weele and B. R. Johnson Nature (2025) May 1st. vol 641, p34 )

On the other hand, in countries where economic development is still in the future (right side of Figure 1), there is less change in happiness from young to old than in countries with economic leeway. It is noteworthy that at any given time, happiness levels are higher in some countries than in economically developed countries. Dr. Vander Weele and his colleagues state, citing data from another study, that this is likely due to the fact that people in these countries have a stronger sense of emotional connection and a sense of purpose in their society, which contributes to happiness. Results also show that people who attend religious gatherings about once a week tend to be happier than those who do not. In light of this, Dr. Vander Weele and his colleagues suggest that surveys of happiness should include questions that take into account the social, economic, and religious backgrounds in which people live, and that in order to accurately understand the happiness of a place, it is necessary to first understand the various backgrounds.

Surveys on happiness are extremely important in understanding the problems facing a region, and such surveys have already begun in several countries. Dr. Vander Weele and others suggest that by reflecting the results in politics, it will be possible to realize a better society.

Looking at the happiness results by age in Japan (Figure 1), it is surprising that Japan’s happiness levels are lower at all ages than any other country, compared to Australia, Brazil, Sweden, and the United States. Isn’t it especially problematic that the happiness levels are low even among young people and middle-aged people? The key to solving this problem may lie in human relationships. In developing countries, human relationships are closer, which seems to lead to an increase in happiness, so it seems important to reduce people’s sense of isolation in Japan as well and create a more solidarized society. Even in Awaji Island, where the birthrate is declining and the population is aging, further strengthening human connections may lead to a sense of well-being.